The self-inflicted wound that French political life has become reached a new nadir before Christmas, with the swift resignation of Michel Barnier (which had appeared inevitable ever since he took office) and his replacement by the veteran centrist François Bayrou.

The BBC, which one assumes has no dog in this fight, described Mr Bayrou on the day of his appointment as ‘respected’.

It is a measure of his ability to command ‘respect’ that he has only just been absolved of allegations of embezzlement, accusations of which caused him to leave his post in President Macron’s first administration in 2018.

As a man who has always stood mainly for the principle of not being either of the left or of the right, Mr Bayrou represents perfectly the flannel, indecision, vagueness and inaction that have largely brought France to its present state.

A precarious position

Anyone who wanted to put money on his still being in office by the summer would benefit from a serious rethink.

Mr Bayrou has before him the utterly impossible task of finding a consensus within a National Assembly composed of groups who broadly hate each other.

The people keeping him in office, for the moment, are members of the Rassemblement National, who have indicated they will continue to support him so long as he does something to tackle the ever-growing cost of living, and the ever-expanding problem of illegal migration.

Cutting France's deficit

On top of that, he has the far from negligible problem of constructing a budget whose basic precept – cutting public spending and therefore the deficit – the hard leftists of La France Insoumise bitterly oppose.

Mr Bayrou talks of the ‘moral’ imperative of cutting France’s debt, the moral element being how wrong he feels it would be for the delinquent generation currently in power to leave this massive obligation to their children and grandchildren to shoulder.

Like so many of France’s politicians, he seems to have reached this position relatively late in life: but he is right.

There are two other reasons why France cannot continue to have levels of debt of the present size.

First, it is against European Union fiscal rules, and if France aspires to remain a member of the club it is going to have to pull itself into line.

The EU stipulates a 3% deficit ratio and a 60% debt ratio, relative to gross domestic product. France’s deficit is around 5.5% and its debt ratio is 110%.

Cutting France's spending

Second – this is closely related to the first point – maintaining existing levels of public spending only makes things worse, and with interest rates comparatively high by 21st Century standards the cost of servicing this debt is an enormous drain on the French taxpayer.

As in all economies where such situations prevail, the productive sectors of the economy are drained for the benefit of the unproductive sectors.

The growth that France, and the EU in general, needs is therefore elusive; and it will remain so, for as long as France is determined to live beyond its means.

Two aspects of expenditure are an especial drain on France’s increasingly scarce resources.

By comparison with most other similar countries, France has an over-generous welfare state and an over-manned bureaucracy.

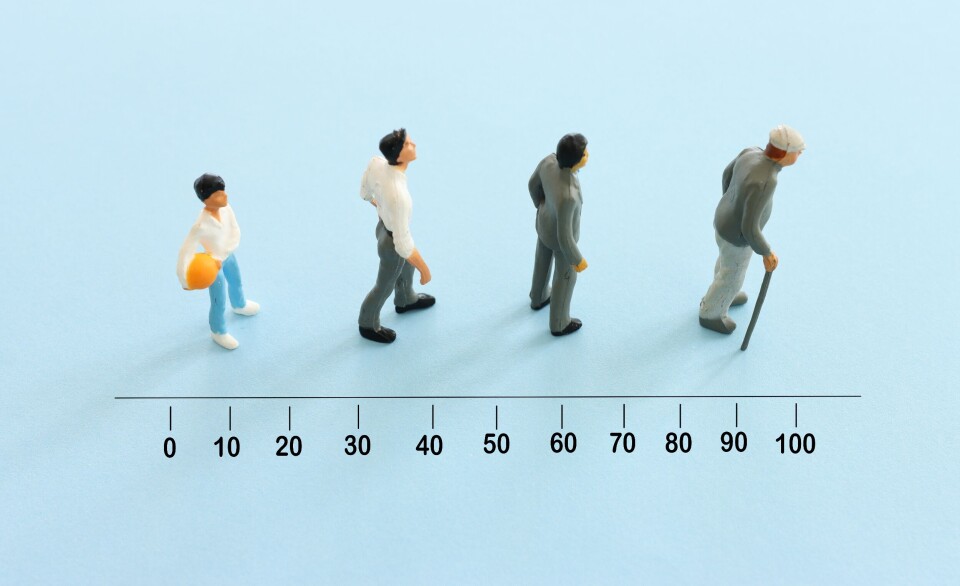

For example, although the retirement age in France is moving up to 64 (with great controversy), it is still possible to retire on full state benefits at 62.

In the United Kingdom the age is 66, and moving rapidly to 67. It is 66 in Germany, 67 in Italy and 67 in the Netherlands.

The political problem Mr Bayrou, like others before him, faces is that a strong lobby, represented largely but not exclusively by La France Insoumise, refuses to countenance an end to borrowing excessive amounts to keep them in the style to which they are accustomed.

However, it also refuses to see that funding a lavish welfare state funded out of higher taxation will simply drive wealth-creators out of France.

'President Macron should resign'

The present situation is entirely unsustainable, but too many French people, and their elected representatives, refuse to accept that this is the case.

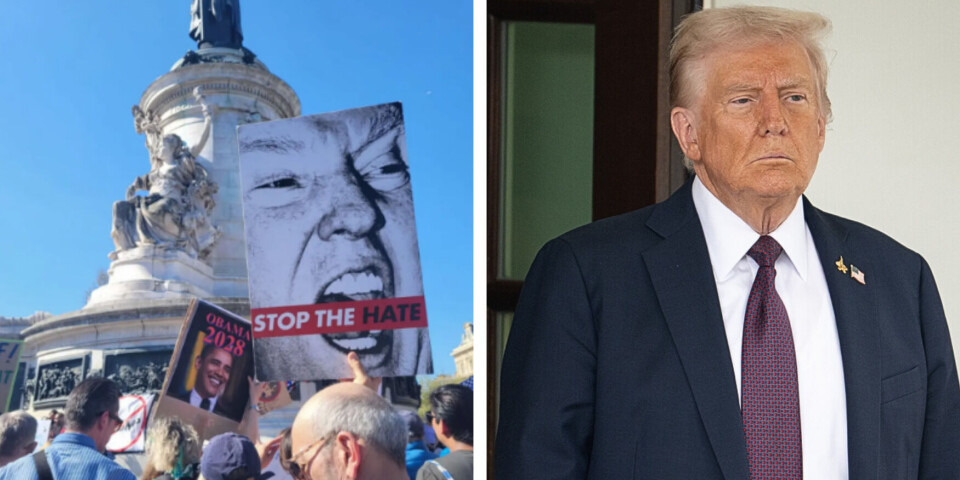

The real architect of the current mess is President Macron, whose decision to call an election last summer in an attempt to torpedo the resurgent Rassemblement National backfired spectacularly. Mr Macron, who has just appointed his fourth prime minister in a calendar year, has learned nothing from his mistakes.

Having lost Mr Barnier, he managed to appeal to the ambition and vanity of a former crony to secure a replacement, however temporary that replacement turns out to be. For all the use Mr Bayrou is likely to prove to be, Mr Macron might as well have appointed Pierre Mendès France or Georges Clemenceau.

Yes, they are both long dead, but there is no guarantee a living and breathing prime minister is going to be any more effective than they might be.

During the negotiations that preceded the appointment of Mr Bayrou, representatives of LFI or the RN were not included.

It may well be that both parties are intractable and inflexible, but they were, and are, an inherent part of the problem.

Until they join such talks, little or nothing can be achieved. It is more than two years until Mr Macron’s term is due to end.

He can go on appointing four, five or six prime ministers a year, making a laughing stock of himself and his country; or he can take the obvious step a man of honour would take and resign, and let the French people put someone new in charge of their country’s direction.

Perhaps if he calls parliamentary elections in the summer – the earliest he can do so - and is thwarted again, then he would admit defeat.

What he cannot see, in his arrogance, is that to wait until then is to prolong France’s suffering.

What do you think about France's current political upheaval? Let us know at letters@connexionfrance.com