What is France’s ‘intime conviction’ legal concept used to reach verdict in Cédric Jubillar trial?

Unique approach to murder trial without a body that transfixed France

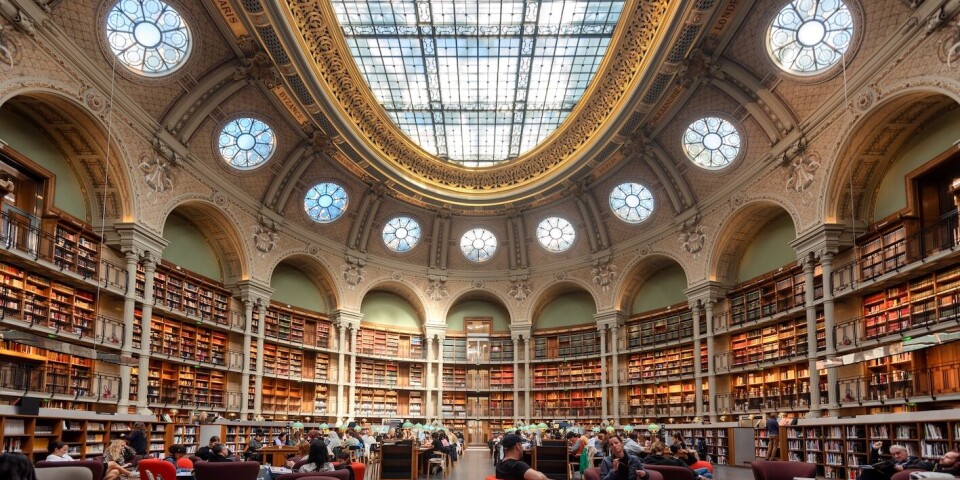

In France’s cours d’assises, judgments are passed by a panel of six randomly selected jurors and three professional judges.

Bruno Bleu / Shutterstock

A French court has sentenced Cédric Jubillar to 30 years in prison for the murder of his wife who disappeared from their home in December 2020 despite prosecutors having no crime scene, no body and no confession.

The verdict, delivered on Friday, October 17, by the Tarn Cour d’assises (Court of assizes or Criminal court) in Albi after six hours of deliberation, rested not on material proof but on what French law calls the principle of intime conviction – the inner belief of jurors and judges that the accused is guilty.

A disappearance without proof

Delphine Jubillar, a 33-year-old nurse and mother of two, vanished during the night of December 15/16, 2020 from the couple’s house in Cagnac-les-Mines, near Albi in south-west France.

Her husband told police that she had gone out in the middle of the night wearing a white coat and carrying her phone.

An extensive search operation failed to locate her.

Over time, investigators gathered indirect evidence suggesting a volatile relationship and possible violence.

Items such as a broken pair of glasses, witness statements about shouting, and conflicting timelines were presented to the court.

Cédric Jubillar, a decorator, was charged with murder in 2021 but has always denied any involvement.

He remained in custody for more than three years awaiting trial. The prosecution argued that he killed his wife in a fit of anger as she prepared to leave him.

What is ‘intime conviction’?

The French system does not require proof ‘beyond reasonable doubt’, as in English or American law.

Instead, the criminal code directs jurors and judges to decide according to their intime conviction – literally, their inner belief – after hearing the evidence and the defence.

The expression, which appears four times in the code but has no formal legal definition, dates from the 18th century.

It instructs jurors to examine their consciences and decide freely, without fixed rules about what counts as sufficient proof.

Before the French Revolution, evidence was assigned numerical values: an admission counted as a full proof, a witness statement as a half-proof.

Modern law abolished that hierarchy. All forms of evidence now carry equal weight, and their significance depends entirely on the court’s collective judgement.

“The law does not ask judges or jurors to account for the means by which they have been convinced,” states article 353 of the criminal code.

“It asks them to seek, in the sincerity of their conscience, what impression the evidence and the defence have made upon their reason.”

How the verdict is decided

In France’s cours d’assises, judgments are passed by a panel of six randomly selected jurors and three professional judges.

After final statements, they retire to deliberate in private, reviewing only what was said aloud during the trial – a rule known as the principe d’oralité.

Each member votes by secret ballot. A conviction requires the agreement of at least seven of the nine members.

In appeal courts, where twelve people sit, eight votes are required. Breaching the secrecy of deliberations is punishable by up to a year in prison and a €15,000 fine.

Although jurors are guided by their conscience, the court must still provide a written explanation of its decision.

Since 2011, the presiding judge has been required to produce a ‘statement of reasons’ within three days, summarising the decisive elements. This allows the defence to contest the verdict on appeal.

The role of doubt

Supporters of the system say intime conviction gives the court flexibility to weigh complex cases.

Critics argue that it can open the door to subjective reasoning, especially when physical evidence is lacking.

“The doubt must always benefit the accused,” said Jenny Frinchaboy, lecturer in criminal law at Paris-I Panthéon-Sorbonne. “If the intime conviction is not certain, the accused must be acquitted.”

She noted that this principle led to the acquittal in 2010 of Jacques Viguier, accused of killing his wife in a similar case without a body or confession.

Changing role of juries

Since 2023, many serious crimes – including rape and aggravated theft – have been transferred to new cours criminelles départementales (departmental criminal courts), composed only of professional judges.

Only the most serious offences, such as murder, and appeals now come before the cours d’assises with lay jurors.

“Jurors brought a fresh and sometimes more lenient view,” said Ms Frinchaboy. “But even without them, intime conviction remains the standard by which every verdict must be reached.”

Jubillar, who maintains his innocence, has announced his intention to appeal, giving another court the chance to reach its intime conviction.